[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: Lola Akinmade Åkerström is a Nigerian-Swedish author and award-winning travel photographer based in Stockholm, Sweden. The views expressed in this commentary are her own.

Stockholm, Sweden

CNN

—

When mirrors show us how we look, we adjust what needs to be fixed. We don’t break those mirrors simply because we won’t accept our reflection.

I remember the exact line from a reader’s letter that moved me to tears. You know, the type of sobbing that purses your mouth into an ugly pout.

“You allow them to be strong, vulnerable, brilliant, messy,” she says of my characters, “and yet you command your audience to always remember that all those roller coasters of experiencing romance, loss, love, success and emotions are not only reserved for white bodies.”

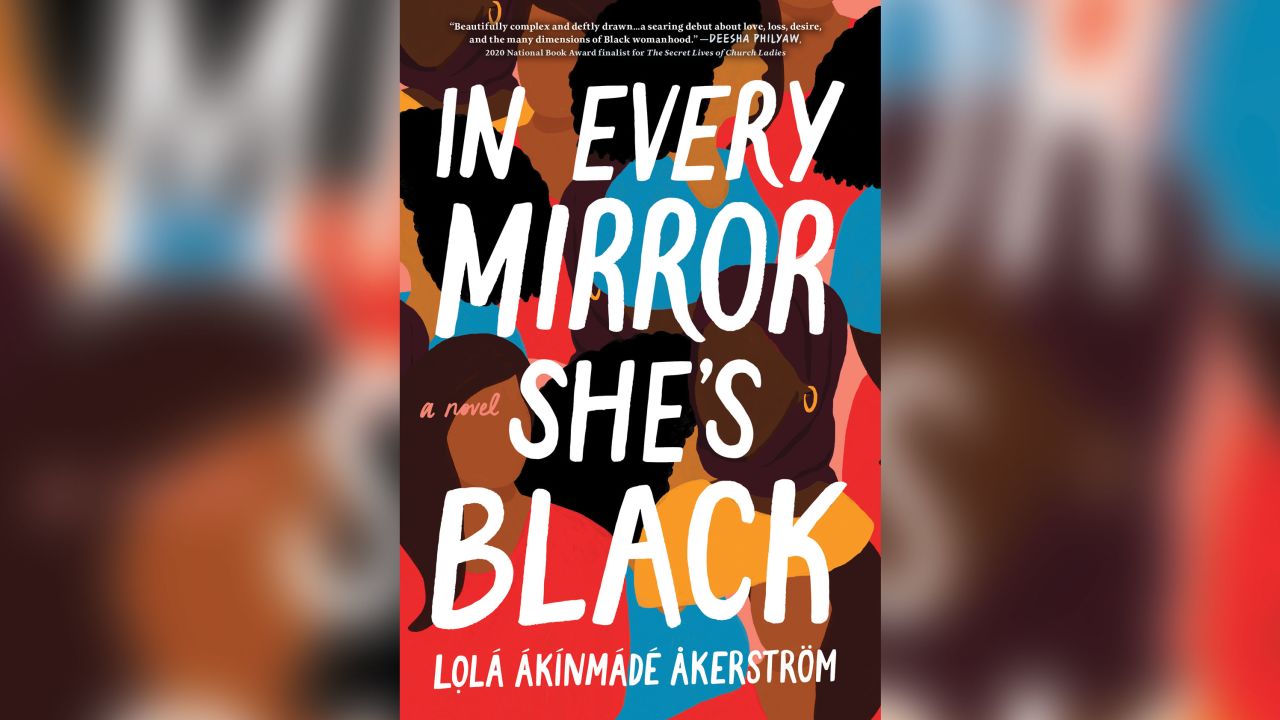

This is just one of dozens of personal letters I have received from readers across the globe who feel seen in my three fictional protagonists: Marketing executive Kemi, model-turned-flight attendant Brittany, and refugee Muna, whose stories form the core of my novel, In Every Mirror She’s Black.

While the journey to publication was challenging after so many rejections, we knew once we got past the industry gatekeepers, the book would resonate fully because it is raw, real, and transparent.

We were right.

From being displayed on Times Square as a Good Morning America Buzz Pick and being named by The Independent UK as the most thought-provoking book by a Black author to being an Amazon Editors Pick and Apple Books Pick, amongst other memorable moments. We have four global publishers, and the German edition will be published later this year.

As with anything raw and real, the response to my book has been wide ranging. From those who feel completely seen and heard, to those who refuse to accept a more nuanced picture of a country they idolize.

“So, how has this been received in Sweden?”It doesn’t take long before this question pops up during any interview. My answer is always met with surprise when I share that a book written by a naturalized Swede about Black women and Swedes set in Sweden, has yet to be translated into Swedish.

“Why?”

That was the question I pondered for months when we tried to sell the book. We were either met with cold silence or one-liner, not for us, responses.

The most insightful answer came in a wordier response from one of the country’s largest publishers. While they appreciated my storytelling skills and insight as an “outsider” into Swedish society, they wanted me to cut out scenes from my character Muna’s story.

Muna is a Somali refugee. Her story was inspired by real people I met while spending two years visiting a now-closed asylum center as a photographer, listening to their stories, feeling their fear, pain, hopes, and dreams.

The publisher was concerned her story would make the Swedish audience uncomfortable.

Part of my five paragraph response to them was: Which Swedish audience? White Swedes or non-white Swedes?

Already the most invisible character within society in the book, in essence, they wanted me to minimize her existence for their comfort, while discounting the experiences and feelings of the marginalized.

As a travel writer and photographer, I regularly extol Sweden’s cultural and panoramic beauty I love so much through words and photography for various publications. I’ve also delved deep into understanding the Swedish psyche in my book LAGOM, which is translated into 18 foreign language editions, ironically except into Swedish, but I’m not surprised.

This unflinching need to always remain perfect and flawless is what continues to add to the tensions between various factions within society and an increasingly confusing global image.

Similar to every single character in my book, we’re all multi-dimensional, richly diverse, complex and messy human beings. We offer each other constructive feedback because we want each other to grow into better versions of ourselves.

Unfortunately here, any slight whiff of perceived criticism is considered an affront to the glass paradise that Sweden has built around its image. So, many people choose to silence their own voices and keep their lived stories untold, or risk exclusion from society.

Two things can always be true: You can be a world leader when it comes to certain issues and still have a lot of work to do in your own backyard.

For you to work on issues, you actually have to publicly acknowledge them. The UN issued an official report last year, urging Sweden to work on its systemic racism. That report was essentially glossed over here.

Sweden is very progressive in many ways. This cannot be argued and I love my adopted home for this.

The Swedish version of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists is distributed freely to high school students across the country. The publishing industry is quick to bring in foreign authors and translate books that discuss trauma and heavy subjects set in other countries, except Sweden.

Because bad things only happen somewhere else, not here.

“So why don’t you self-publish it in Swedish yourself?” is the follow-on question I often get.

I could. But I choose not to, because that is essentially giving the publishing industry a free pass. Imagine if every marginalized Swedish author had to keep self-publishing their own work just to make their voices heard in a society they also actively contribute to?

This issue is so much bigger than my fictional novel and personal desires.

Most self-aware people make the necessary changes if a mirror shows them there’s a sliver of spinach trapped between their front teeth.

It takes a special kind of hubris to break that mirror instead and strut out confidently with the spinach firmly stuck, proclaiming there’s nothing to see here.

“A bitter pill to swallow,” my dear reader goes on to say in her letter, “but one that allows for relearning, unlearning, and finally healing.”

[ad_2]